For my paternal grandfather, there was no such thing as a bad day.

“Beauty-full day!” he’d say just like that to anyone within earshot, as he puffed on his unfiltered Camel cigarette.

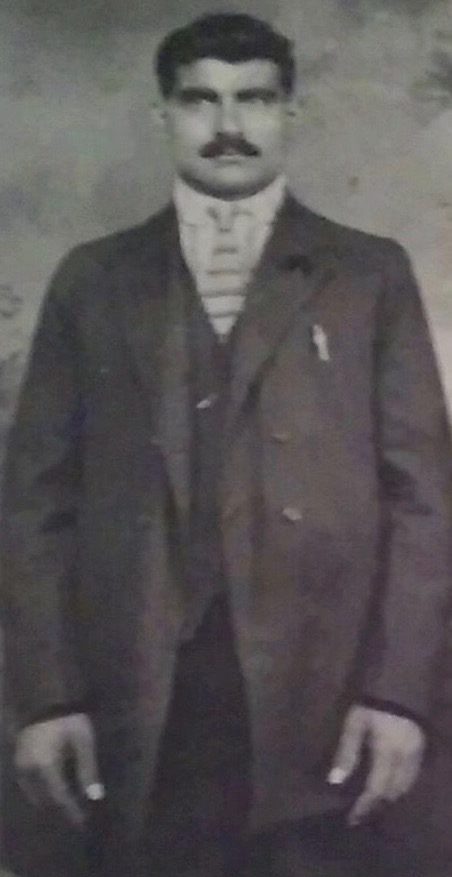

With glasses and a thick mustache, he always sported a ratty beige cardigan sweater, even in summer. I don’t remember him wearing anything else.

More than 100 years ago this month, Esper John, my father’s father who was known as Jiddu (grandfather in Arabic), fled Damascus, Syria. He had his reasons.

From the many stories passed down through the generations, Jiddu mostly wanted to avoid being conscripted into the Turkish Army. As a Christian, he longed to flee the Ottoman Turks’ oppression and their Muslim dictator.

Along with all of that, he also dreamed of seeking a better life and leaving economic hardship behind.

The promise of fulfilling that dream was in America. Despite overwhelming odds against him, Jiddu set out for the courageous journey, not surprisingly, as we learned, just in time.

In 1918, after 400 years of oppression, the Ottoman Empire toppled when British and Arab troops captured Damascus. Syria’s new leader Emir Faisal was a pretty cool guy, so he was proclaimed king.

Indeed, it was Faisal’s desert army with British war hero T.E. Lawrence (yes, that “of Arabia” Lawrence) who helped make victory possible. Sadly, the French didn’t really like Faisal, so a month later, he was overthrown and fled. The French took control in 1920.

Back then, immigrants such as my grandfather were considered a threat to the United States. They were branded ignorant and dirty. It saddens me to read the same sorts of epithets aimed at immigrants these days.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

My folks used that phrase often, usually shaking their heads in unison. I brushed it off as typical parental blather. It wasn’t.

Born somewhere in Syria, Jiddu’s actual birthdate has always been in question. On his U.S. Registration Card, it says he was born February 9, 1895, in Jakowat, Syria, a citizen of Turkey. Other documents cite November 17, 1889, in Jouighat (likely a variation of Jakowat), and even November 23, 1901, in someplace called Matchaa.

My Syrian friend and hairdresser, who was born in Lebanon, has a theory. “We’re not so good with birthdates,” she said. No kidding.

Let’s go with 1889 because it works with my math.

Jiddu’s original Arabic surname, Hanna, translates to John in English. Syrians often used their father’s first name as a last name, from the tradition of calling someone “ibn,” meaning “son of.” As in, Esper, son of John. That’s why so many Syrians have first last names, such as Abraham, Thomas and George.

The earliest documentation for Jiddu is a ship manifest (below) for the SS Chicago dated August 30, 1910. The name on the list is Esber Hanna. Misspellings were not uncommon since foreign names were often translated phonetically.

Apparently, he was held as an Alien for Special Inquiry, which probably was even scarier than it sounds.

There’s no indication what port the ship left or when and where it arrived. But it was a French Line. If this were Jiddu, he would have been about 21, using his 1889 birth year. Here’s what we know:

- He was traveling alone.

- He ate 10 meals during the voyage.

- He was detained for an LPC, or likely public charge. This meant he had little or no money and would probably need government assistance.

On top of all that, he couldn’t speak English, read or write. The official signature on his U.S. Registration Card was a large, thick black “X” resembling a child’s scrawl.

It breaks my heart to think of what it took for him to come to America. Oppression forces you to find courage.

Yet another name and birthdate appears on his U.S. Petition for Naturalization papers: Esper John Alias Esper Hanna born in 1901. So, my illiterate grandfather had an alias. He also worked as a clerk and lived on Bridge Street in Brownsville, located in southwest Pennsylvania.

Here’s where it gets even more confusing.

The naturalization papers say he emigrated from Le Havre (a commune in France’s upper Normandy region, where the Seine River meets the English Channel, just west of Rouen) on August 5, 1920. Eight days later, this single man of about 20 arrived at the Port of New York on the vessel Rochambeau.

Honestly, sometimes I’m not sure what to believe. Did he sail here in 1910? Or was it 1920? Was he born in 1889? Or 1901? In a weird way, it doesn’t matter. He got here.

My paternal grandmother, Jamile Shami, known as Sittu (Arabic for grandmother), had her own dramatic story of leaving Syria. While working as a translator for a Russian czar, she rejected an arranged marriage to some guy she couldn’t stand. Her well-to-do parents were so disgraced, they shipped her off to America.

Sittu ended up in western Pennsylvania, where she met my penniless grandfather. They fell in love, married on June 5, 1921, and … the rest is history.

Wasting no time to establish a new life for his family, Jiddu declared his intention to become a U.S. citizen on January 9, 1922. His oldest son was born February 21, 1922.

That child was my father.

Oddly enough, I started writing this piece with the intention of promoting a traveling exhibit that tells the moving stories of refugees from Syria and Iraq.

The Arab American National Museum in Detroit recently premiered “What We Carried: Fragments & Memories from Iraq & Syria,“ at the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, one of America’s most iconic and significant historical sites. The exhibit runs through September and is expected to draw nearly 750,000 people.

What We Carried celebrates our shared humanity and focuses on those who left everything behind in hopes of creating a better future for themselves and their families in a setting free of war and uncertainty.

Since 2003, more than four million Iraqis have left their homes and relocated. Many sought refuge in Syria, only to find yet another dangerous situation. About 140,000 of these refugees have immigrated to the United States, the majority with nothing more than the clothes on their backs and a small memento as a reminder of home.

Then I got to thinking about my Syrian grandparents and how they got here.

I wonder what they carried.

3 Comments

Maureen Dunphy

Loved reading about your Jiddu, Jen! So many different stories of how we all ended up Americans. My family, on both sides, came mostly from Ireland. They were not welcomed. At the time of their arrival, employment advertisements often included the phrase “No Irish need apply.” The piece of writing I read right before your posting of today was: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/24/us/border-migrant-children-detention-soap.html What are we doing?

On a happier note, thank you for alerting folks to the Arab American National Museum. My husband’s mom was Lebanese (the daughter of a Yezbick and a Joseph; the award-winning poet Laurence Joseph (b. 1948), also a Professor of Law, is of the same family. According to his entry in Wikipedia, “Joseph’s grandparents, Lebanese Maronite and Syrian Melkite Eastern Catholics, were among the first Arab Americans to emigrate to Detroit, where both Joseph’s parents were born.” ). My daughters grew up enjoying Lebanese food at their grandma’s Ferndale home. For our wedding anniversary two years ago, my eldest got us a Yalla Eat Culinary Walking Tour from the Museum, which included a tour of the museum’s exhibits and visits to a number of great restaurants in the area. Fascinating–and very tasty–afternoon!

Kori Blessing

I could read about our Jiddu, over n over! It’s hard to know what all he went thru to get to America. I miss his toothless smile, friendly wave, and that sweater! It’s a Beauty-full day!

Connie Rizzotti

Love reading your stories. So interesting. Keep them coming!