In her later years, my Italian grandmother couldn’t remember what day it was or her own name. Yet before leaving the house, she never forgot to grab her black leather pocketbook with the single-snap closure that safely housed her dentures, balled up in a slightly-used Kleenex that ultimately ended up being thrown in the trash. By her.

One minute Nonna would be sitting in her tattered living room chair, and the next she’d be out the front door, down the crumbled cement steps and halfway up the block, on a mission to go home. We soon figured out that “home” meant back to Italy, where she was born on this day, October 28, 1890.

Several times a week, day and night, you’d see my mother running down Wilfred Street chasing an elderly speed-walker clutching her purse. After retrieving Nonna, my mother would search my grandparents’ house until she found the missing teeth. Sometimes, when they didn’t turn up right away, she enlisted my help. Turns out, instead of tossing the dentures in the trash, Nonna sometimes would hide them elsewhere, say, in the pocket of her house dress. She was quite resourceful.

So, Happy Birthday, Nonna.

Domenica Bonino came from Biella in northern Italy’s Piedmont region, which borders France and Switzerland. The small town sits at the foot of the Alps, about 50 miles northwest of Milan.

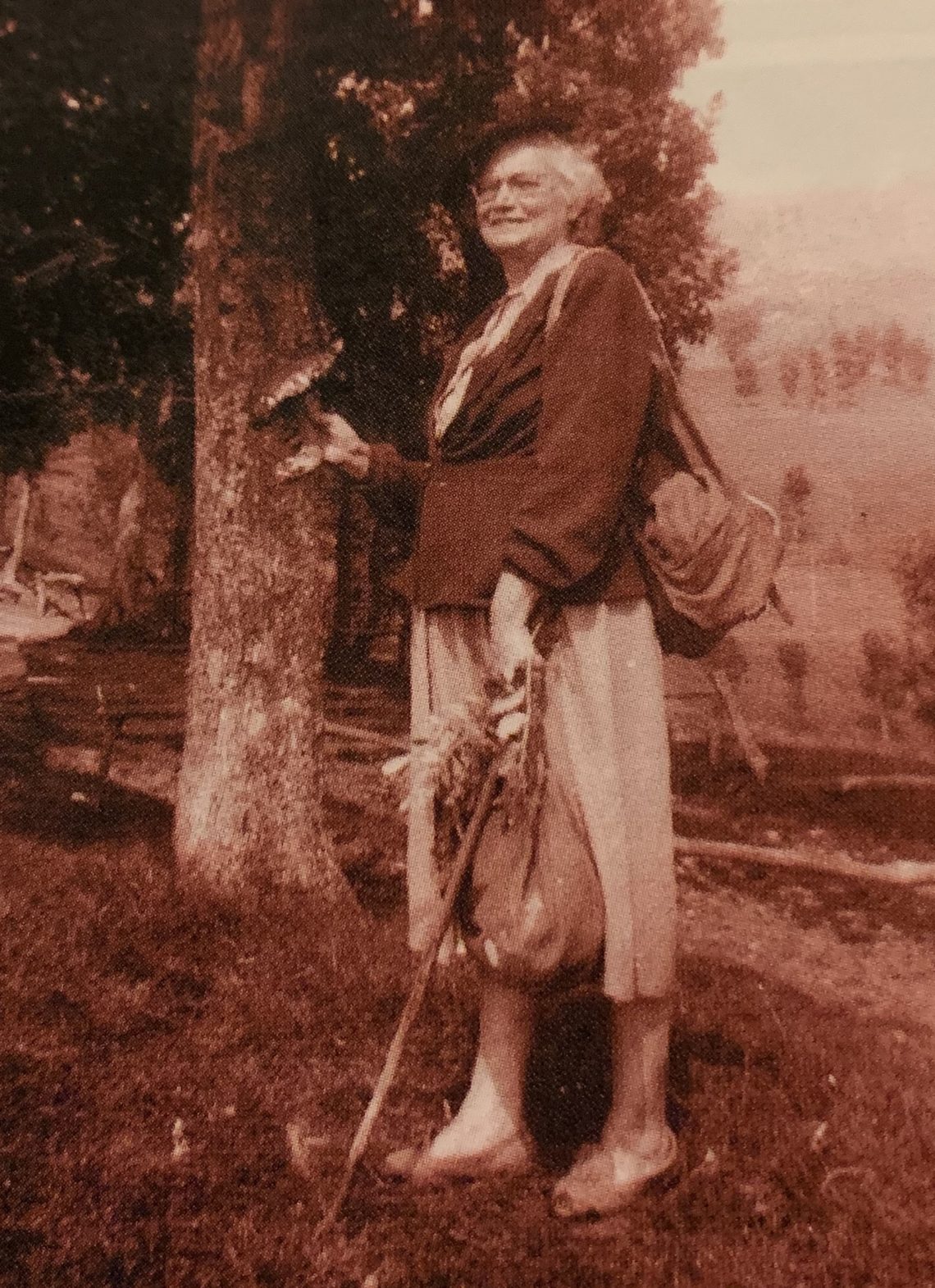

One of six children, Domenica had no formal education, and as a girl she worked in a local textile mill. She learned to read Italian and English as an adult. (In this post’s main photo, that’s her picking mushrooms on a visit to Italy in 1960. She was 70.)

In 1912, she married Luigi Guella, a 23-year-old soldier also from Biella. In 1920, Luigi sailed to America, in search of a better life for his growing family. He found steady work as a laborer in an Ohio brickyard and sent for his wife in 1922. Domenica left Italy with their two daughters, Enea, 8, and Elia, 22 months, accompanied by her brother, Giovanni, who was 30. The Guellas settled in Alliance, Ohio, and had another daughter, Nores, in 1924. The middle one, Elia, was my mother.

In the late 1960s, my grandparents moved to Detroit’s east side to be near us. They lived downstairs in a modest, two-story brick home that had an upper flat connected to the main house by wooden stairs coated with chipped gray paint. As a youngster, I’d hide on those steps and listen to my grandparents playing cards in their kitchen. My grandfather, Nonno, would pretend to scold me about eavesdropping, but then he’d wink. Eventually, they taught me how to play Marianna, an Italian card game similar to Briscola, the more popular version.

As for Nonna, her forgetfulness became evident when she left the kitchen stove on, pots of water boiling over, eggs frying into nothingness and spaghetti sauce burned beyond recognition. It’s a miracle no one ever got hurt. Her condition worsened with age. Doctors called it senility back then.

In the early 1970s, we moved from a decent-sized house in Detroit to that tiny upper flat, so we could take care of my grandparents. The sacrifice my folks made left a lasting impression on me, and taught me the importance of family and unconditional love.

I remember the strain that caring for Nonna put on my parents and our small family unit, since my older sisters already were married. But Mom kept going, until it was just too much. After my grandfather’s death, we moved out of that flat into a larger house. Never quite settled in those new digs, Nonna would lie awake, night after night, yelling, “Mama! Mama!” She wanted to go home.

It nearly killed my mom to put her own mother in a nursing home. No doubt that’s part of the reason she visited her twice daily for nearly 10 years. Nonna never knew how much her daughter had sacrificed, but she liked her new home, walking back and forth in the long hallways until nap time. By this time, she didn’t know any of us at all.

“That Elia never comes to see me,” Nonna would say in Italian, staring into her devoted daughter’s eyes. “Mom, I’m here,” Elia would reply. Broke my heart.

I often wonder why I remember all of this so clearly some 50 years later. Perhaps it’s because I lived it. How could I not remember?

Nonna died in 1980 at 90 years old. Her heart simply gave out.

She finally made it home.

10 Comments

Joanne Schenten Skupin

My family has dementia. I’m trying several methods of prevention.

I’ll let you know the details if I’m succesful.

Jennifer John

Just keep doing what you’re doing, Jo. Time for another lunch, don’t you think?

Connie

Love your stories. You should write a book — it would be a best seller!

Jennifer John

I’ll need an agent, Con.

Judy

OK. This is my new favorite. We all have these stories, but you are the storyteller for all of us.

Jennifer John

Thanks, Judy!

Mary Suhonen

LOVE LOVE LOVE GREAT MEMORIES. THANK YOU!

I went through some of this with my own mom.

Thanks again. Enjoy.✌🏼❤️

Jennifer John

Thanks, Mary!