“You fixed yourself.”

Those were three little words I wasn’t prepared to hear on the last Wednesday in August.

Here I was at a local hospital in out-patient cardiology pre-op, hooked up to an electrocardiogram machine with two white patches stuck to my chest and back, being prepped for something called cardioversion, a quick, low-energy shock to restore my heart’s normal rhythm.

I felt like a human battery about to get boosted by a tow truck driver in a white coat. Which I was.

The IV port planted in the crook of my right arm longed for the perfect dose of “conscious sedation” to make me sleepy and unaware of the entire procedure until I woke up refreshed, relaxed and (we hoped) regular.

I could have used this stuff when I was working.

“You fixed yourself,” the same voice repeated.

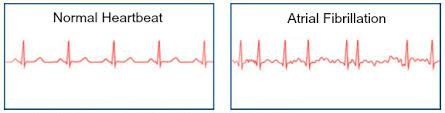

The ECG, which records the heart’s electrical signals, apparently registered what looked like a sinus rhythm, which has nothing do with your nose and everything to do with your heartbeat.

Someone else thought I was still in A-Fib. Another deemed it “not full-blown A-Fib but definitely a flutter.”

Whatever it was, I just wanted to go home.

“So, our work is done here,” I said. “You think my insurance will waive the co-pay?”

Not so fast.

Back story: I have been in atrial fibrillation for about 14 days now. It’s more prevalent than you think with all of the crap we Americans eat and how little we exercise. But A-Fib can also be inherited.

Guilty as charged on all counts, your honor.

According to those smart gluten-free cookies at Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, A-Fib is one of the most common types of heart rhythm conditions. During A-Fib, the top chambers of the heart beat in an irregular rhythm, out of sync with the heart’s lower chambers.

When your heart beats faster than normal for a long stretch of time, the muscle gets tired. Some people experience no symptoms at all.

Others, like me, have a triple-digit resting pulse, batting average blood pressure, fatigue and drenching flop sweats. Not necessarily in that order.

As I understand it, my heart’s electrical signals are disorganized. As a self-described neat-freak who may or may not alphabetize her spices, this messy tidbit is a bit hard to swallow.

Speaking of the esophagus (see what I did there?), before my scheduled cardioversion, I underwent a T.E.E., short for transesophageal echocardiogram, which is another way to see what’s going on inside your chest. They sedate you, insert a special probe containing an ultrasound transducer and use sound waves to create pictures of your heart.

I have no idea what that means.

Think of it as a form of internal Doppler radar. (By the way, my doc predicts rain for most of this holiday weekend. Of course, I’m kidding. But you may want to reconsider that Labor Day BBQ.)

Unfortunately, the TEE showed a small “something” in the upper chamber of my heart. The cardioversion will have to wait. They suspect the blood thinners I’ve been on for only a week didn’t have enough time to do their job, and I’m grateful they noticed it and erred on the side of caution. When zapped, this “something” could dislodge and cause a stroke.

The last time I had an A-Fib episode was in the fall of 2017. At least I think so. My internist discovered it during a routine visit. My blood pressure was way too high, and my resting heart rate was 130.

Turned out I was in full-blown A-Fib and had a leaky mitral valve that was repaired on May 31, 2018. The state-of-the-art surgical technique, called annuloplasty, tightens, reshapes and reinforces the stretched-out ring around the mitral valve. It was my second open-heart surgery in less than 20 years.

It was no picnic, but it worked. Or so I thought. Turns out, there’s no cure for A-Fib. Who knew?

For the past four years, I’ve been fine and A-Fib-free. That is, until a couple of weeks ago when I started having weird symptoms (see above) and didn’t feel like my usual lovely self.

For now, I’ll take my medicine and avoid possible A-Fib triggers such as stress, caffeine and red meat. Pray the beta-blocker and blood thinner do their job, and my cardiologist will attempt another TEE/cardioversion in a month or so. Fingers crossed.

Back in 2018, my cardiac surgeon, Dr. Steven Bolling of Michigan Medicine, said this after our final post-op visit: “What I tell my patients is when I’m dead, I’ll be a pile of dust. When they’re dead, they’ll be a pile of dust with a little ring. It’ll be there. It’s part of them.”

Sweet talkin’ guy. Maybe not the sort you’d want to have a beer with, but the dude’s nothing if not direct.

P.S. Thank goodness for Apple Watches. Seriously. At first, I doubted its accuracy for my resting pulse rate – “130? I’m folding a napkin!” – but then realized it was indeed correct. We’re both getting the latest version this weekend. It does everything but buy you a drink. Probably for the best since alcohol triggers A-Fib. Cheers!

18 Comments

Julie M Sayers

Wow! I am really sorry you are going through all of this. Hang in there!

Jennifer John

Thanks, Julie.❤️

Connie Rizzotti

Wow. Hope you’re doing OK.

Jennifer John

Thanks, Con.❤️

gramcracker8191

Brilliant as usual sister and a reminder for everyone to listen more seriously to the signals our bodies are sending us. The good Lord gave us two ears and one mouth for a reason. ❤️

Jennifer John

Thanks, sis. Are you channeling Dad?❤️

Vicky Lettmann

Hearts do matter! So sorry you’re going through this stretch. I believe in the Apple Watch. And, I too have a leaky valve. Take care! ❤️

Jennifer John

Must be a blogger thing! I’m thoroughly enjoying your book of poetry. Thanks, V.❤️

Judy Harden

Jen, I love your attitude and your writing. Please take care, and keep wearing that Apple Watch! Miss you.

Jennifer John

Thanks, JH.❤️

maureenbaudhuin

How is it that you make medical stuff fun to read, Jinny? 🙂 So relieved that your situation is manageable and that you’re in good hands!

Jennifer John

Thanks, Mo. I just make stuff up!😝❤️

emily

You’re such a trouper! (And now I’m paying more attention to that BPM number on my watch 😊 )

Jennifer John

Brava! Thanks, Em.❤️

Cindy Guerrieri

Glad you’re on it. Have to be very self aware and our own best advocate when health is concerned.

Jennifer John

You got that right. Thanks, CG.❤️

RYZ

🍎 ⌚️❣️ Thankful you pay attention to your body and do not “fluff” things off. That ticker is happy you take such good care of it – 💪🏼

Jennifer John

Thanks, RYZ.❤️